If your first reaction to the name Camilo Rodriguez is “who?”, I get you. Even if you are a deep lover of AfroCuban music, who knows the names Beny Moré, Miguelito Valdés, maybe even Orlando “Cascarita” Guerra, you might not know who Camilo was or what he meant to AfroCuban music.

When I first started visiting Panama in the early 2000s, I would find among the hot Panamanian Salsa records (and Nuyorican, Boricua, Colombian, Venezuelan, Peruvian etc.) that were revealing themselves to me these semi-corny LPs (see next pic) by Camilo Rodriguez, or celebrating him, on Panamanian labels, usually mostly Boleros and tepid Sones.

With the Pelaos (older cats who were in their prime in the ‘50s and ‘60s, who I was lucky enough to have sat with for hours) his name was spoken with same reverence as other singing greats in the AfroLatin pantheon like Miguelito Valdés, Daniel Santos, Jose Luis Moneró and Beny himself. But even though Camilo (who passed in 1985) was Panamanian, I didn’t get it – I figured he was loved as a bolerista, while I was hunting vinyl by the Soneros, Rumberos and Guaracheros.

I also understood that he was Camilo Azuquita’s (Luis Argumédez Berguido) “Padrino” – Azuquita being the Panamanian singing phenom who burst on the local scene in the early ‘60s singing boleros on a radio show, and was soon snapped up by Boricua heavyweights Kako and Cortijo. Both Kako and Cortijo toured often in Panama, and Azuquita went on to fame in the NY Salsa boom of the ‘70s and later was key to the Salsa boom in France in the ‘80s. Azuquita got the “Camilo” from Camilo Rodriguez. Camilo Rodriguez became “El Gran Camilón.” According to Azuquita’s FB page (He is alive and well in Panama, “Si Seño!“) El Gran Camilón taught his protege vocal technique and how to manage air while singing.

Still, I didn’t get it. Later, when I had the luck to visit Panamanian Bandleader/Singer/Bassist Maximo Rodriguez (QEPD) – leader of one of the hottest groups in Panamanian music, bar none – at his home, I saw a stylized drawing of Maximo singing with Camilo dressed in white guayaberas on the wall, in a Cuarteto with maracas, bass and guitar. I wasn’t clear if Maximo, who was ten years Camilo’s junior, ever actually sang in a Cuarteto with him (I think they did – and Maximo later dedicated an album to him), but what I understood was that Maximo absolutely idolized Camilo. When someone you idolize idolizes someone else, you take note.

Director of the Centro Audiovisual de la Biblioteca Nacional de Panama Mario Garcia Hudson, who I am honored to call a friend, has done excellent research on Rodriguez, especially focusing on his history as Bolerista. Those of us who lean towards the hotter rhythms of the AfroLatin canon might underestimate Boleros, but they were probably a coequal or even greater part of the fame of many of the musicians and orquestas we admire from the first half of the 20th century.

Things started to jell when I was researching a post on Rene Santos, a Cuban who moved to Panama in the late ‘40s and whose recordings I love. I went back to marinating on the movement of Cubans back and forth from Havana, Spanish Harlem, Mexico City, Puerto Rico, Caracas and Panama, and at this point I feel I understand more what Camilo meant to Afro-Latin music generally and to music in Panama specifically. I’d like to share that here.

Thanks in part to research done by Hudson, we know that Camilo Rodriguez was born in the barrio of Paja in Panama City in 1909 to a Colombian father and Martinican mother. His mother Margarita Lena was employed (as a domestic?) by a wealthy French couple, and this story seems common enough in Panama at the time. Remember that the French were deeply involved in the first attempt to dig the Canal, which ended in fiasco in the 1880s, while Panama was part of Colombia until 1903, and Martinicans were among the many Antilleans (mostly Afro-Antilleans) to be employed doing the dangerous dirty work of digging the canal and its ancillary industries/service needs under both the French and North Americans.

When Margarita’s employers up and moved to Cuba, she followed with a young Camilo. When the couple then left Cuba, she stayed and raised Camilo in Cienfuegos, “La Perla del Sur.” Contemporaries in the Cienfuegos music scene of the 1930s included pianist/arranger René Hernandez of Julio Cueva’s influential Orquesta, and later the Machito orchestra in NYC, and Marcelino “Rapindey” Guerra, a childhood friend of Camilo’s. Hernández was one of big three arrangers developing mambo in the ‘40s including Arsenio and Bebo Valdés. Guerra, another titan of AfroCuban music, was a composer, singer/guitarist, and original member of Arsenio Rodriguez’s conjunto (and a key part of the NY scene from the mid ‘40s on).

Here’s where Mariano Mercerón enters our story. Mercerón was an Afro-Cuban bandleader and Sax player from (Santiago) Oriente, the other side of the island from Havana, with its deep Afro-Spanish and Haitian roots, where the Son and Changui are believed to have originated. Musicians coming from Oriente had flavor. Mercerón led a Cuban version of a North American Jazzband in the ‘30s, called the Piper (pepper) Boys, which he moved to Havana and by around 1940 was Spanish-ized to Mariano Mercerón y sus Muchachos Pimienta.

In around 1942 Mercerón y sus Muchachos Pimienta began recording for RCA Victor, which had phenomenal success with Cuban music through the late ‘20s and ‘30s (including Don Azpiazu’s globe-conquering “El Manisero”) and again in the late 1930s with Orquesta Casino de la Playa. Casino de la Playa, you’ll recall, was fronted by singer Miguelito Valdés, singing songs by the hottest composer of the time, Arsenio Rodriguez. Scholars agree that Casino de la Playa’s 1937-40 recordings revolutionized Latin American music. For more on Valdés, see my earlier article Cugie, Ricky Ricardo and the Real Mr. Babalu .

The Muchachos Pimienta had a young Pedro “Peruchín” Justiz – widely hailed as one of the great geniuses of Cuban dance piano – on piano and handling arrangements. Marcelino Guerra played guitar and brought his hit compositions. Mercerón’s band had saxes, trumpets and a trombone, jazzband style, along with trap drums and bongo. This was one of the two major splits in band formations in Cuban music at the time – the Cuban Orquestas (like Casino de la Playa and Muchachos Pimienta) were based on North American Jazzbands, while the Arsenio Conjunto style concept (as well as La Sonora Matancera etc.) comes from the Son Sextetos/Septetos adding piano and an additional trumpet and piano (and soon after, a tumbadora).

The percussion really stands out in the Muchachos Pimienta recordings, which are remarkably hot for the very early ‘40s – listen to the example of “Nagüe!” below for instance. A Tumbadora may have been added for ambiente during recordings – AfroCuban music expert Harry Sepulveda notes that this was the time when, thanks to Afro-vanguardists like Arsenio, the tumba was being incorporated into more bands despite its “jungle” connotations in the dominant culture.

This generally depended on the venue the band was playing in – Bands didn’t bring the tumba to White society gigs, but they did to Black society gigs or beer halls, and in recording sessions no one could see the color of the player’s skin. As Ned Sublette has noted in his epic Cuba and Its Music: From the First Drums to the Mambo, neither Arsenio (widely hailed as The Godfather of Salsa music) nor Ramon Castro, who recorded (Arsenio’s compositions) with Casino de la Playa on Tres and Bongo respectively, were allowed to play live with the Orquesta because of their color.

The Muchachos Pimienta recorded tens of 78s in the 1942-46 period, including hits such as Marcelino Guerra’s bolero-son “A Mi Manera” and Mercerón’s “El Cantante Del Amor”, the massive guaracha “Pare Cochero” (still a Salsa standard), Mercerón’s composition “Negro Ñañamboro”, Arsenio’s epic “Llora Timbero” and Chano Pozo’s “Nagüe”. Chano was probably the second hottest composer of the time, along with Arsenio, and his “Nagüe” (which loosely translates as “homie” in Cuban Abakuá slang – the song says “Homie, what are you doing around here? I have a lil chick that lives down the street”) became a calling card for two of the hottest singers in the Latin America (in which I include NY) of the ‘40s: Miguelito Valdés and Machito.

We know coming in that Camilo Rodriguez is still remembered for his Boleros, but it turns out he (in duet with Roberto Duany – but Camilo was the lead) sang “Negro Ñañamboro”, “Llora Timbero” and “Nagüe!.”

Wait what? The original recording of “Nagüe” is Camilo Rodriguez?

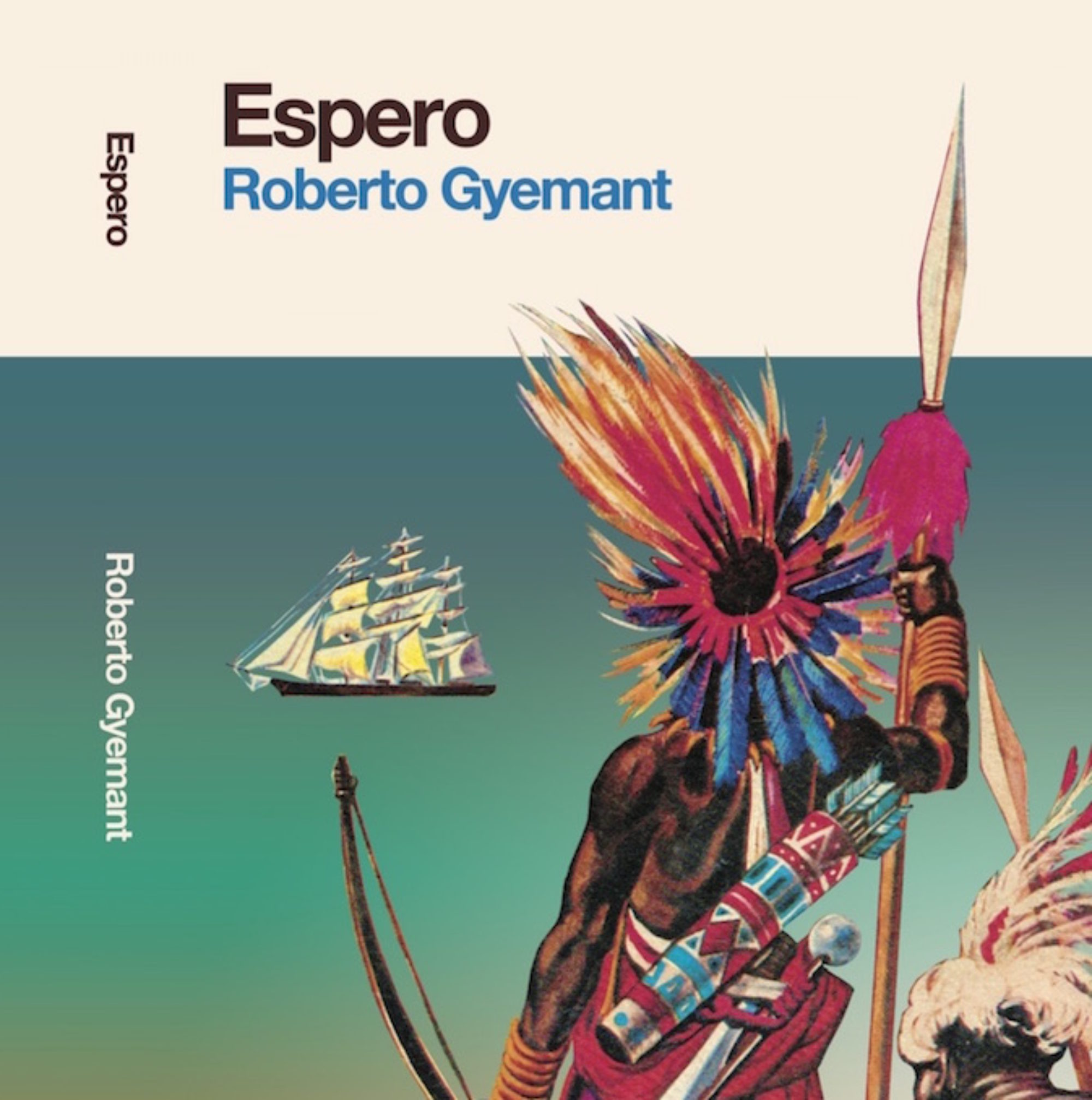

Asi es. By the way, Camilo also played bass for the Muchachos Pimienta, which blew me away to comprehend. See him on the Tumbao CD cover above holding the bass. The bottom of the hottest dance band from Santiago de Cuba, the hottest part of Cuba, was held down by a Colombian/Martinican Panamanian? This man clearly had world-class flavor.

It turns out that the Muchachos Pimienta recordings were so influential in NY (RCA records were pressed in NY, and Spanish Harlem was one of its biggest markets) that Machito’s first band (Machito and his Afro Cubans – the seminal Mambo band of New York in the ’40s-50s) was essentially a copy of Mercerón’s in both instrumentation and repertoire – including “Negro Ñañamboro”, “Llora Timbero” and “Nague!.” (Sepulveda notes that Machito also had a number of Julio Cueva’s tunes – sung by a young Orlando “Cascarita” Guerra – in his book as well).

And not just in NY – likewise in Puerto Rico, Caracas, Panama and Mexico City (the fertile scene for both music and film (“Frijolywood”) that Mercerón would decamp to in 1946). In fact, it also turns out that Ismael Rivera – Maelo, El Brujo de Borinquen, El Sonero Mayor – is on record saying that Camilo’s vocals on those Mercerón 78s from the early ‘40s were a huge influence on him. According to Harry Sepulveda, Cortijo and Maelo were very close to Camilo, as was Rafael Ithier, Pianist and bandleader of El Gran Combo. In fact, Camilo is said to have suggested the song “Irimo” to Ithier (Gran Combo’s original version with a young Andy Montañez singing is a personal favorite).

In 1946, Mercerón dissolves the Muchachos Pimienta and moves to Mexico City. There he was the first to record Beny Moré as a solo singer, and stayed in Mexico until the early ‘50s, when he moved back to Cuba and toured with Beny. He then returned to Mexico for good in 1958. This put him in the company of Miguelito Valdés, Pérez Prado, Francisco Fellové, Silvestre Mendez, Cascarita and other Afro Cuban geniuses/race refugees who moved permanently to the Aztec capital.

Meanwhile, Camilo records a famous session with Pedro Flores – probably the best known Boricua composer next to Rafael Hernández (with whom he performed in Trío Borinquen) – and his Conjunto on RCA, which yielded the massive hits “Si No Eres Tu” and (Te doy mil) “Gracias.” The chisme around this session is that Flores first tried to get legendary Boricua vocalist Daniel Santos to record with him, but Santos turned him down, and further that the band was not Flores’, but actually the recently dissolved Muchachos Pimienta.

And then in 1947, Camilo moves back to Panama.

Let’s check in on some of the other legendary artists we’ve referenced so far: Miguelito Valdés moved to NY around 1940 to sing with Cugat and Machito, and later started his own Orchestra and became an international idol of screen and stage.

Marcelino Guerra likewise moved to NYC in 1944 to play with Machito’s Afrocubans and starts his own influential Orquesta Batamu, and Marcelino Guerra Orquesta, recording sessions on Coda and Verne records respectively. He also rejoins Arsenio, who has moved to the Bronx, enriching a New York scene that explodes through the Mambo-ChaChaCha-Pachanga-Boogaloo-Salsa decades of the ‘50s-70s. Two of my favorite songs of the early ‘60s mambo sound in New York are from Guerra’s pen: Sexteto La Playa’s “Busco Lo Tuyo” (which Marcelino sings on) and Machito and Sexteto La Playa’s “Yo Soy La Rumba”/”Oye Mi Rumba.”

In the late ‘40s Noro Morales and Machito were headlining the Palladium and society gigs in NY (the Titos Rodriguez and Puente were just getting started with their own bands), while Chano Pozo had arrived (1947) and begun his Cubop experiments with Dizzy Gillespie, only to meet a violent death soon after. In Puerto Rico, Rafael Muñoz (with singer Jose Luis Monero) was an Orquesta with international projection. Cascarita was in PR, recording with Pepito Torres’ Orquesta Siboney (with a young Joe Valle). In Caracas, Billo’s Caracas Boys were a carbon copy of Casino de la Playa and Rafael Muñoz’s outfits.

And Panama? Panama was popping. There was diverse nightlife on both coasts (including Calypso and North American Jazz) driven by the hordes of US servicemen streaming out of both ports at the ends of the US’s colonial property in the Canal Zone. Miguelito Valdés was back and forth in Panama – he lived there from 1933-34, playing with bandleader Lucho Azcarraga, and bore a son (Chengue) who would go on to direct a major television channel in Panama. Cascarita was in Panama all the time, and both Peruchín and the great Miguelito Cuní lived there for periods in the 1940s. Beny Moré – an early fan favorite in Panama, before he became popular in Cuba – would play the carnavales in Panama 7 times between 1947 and 1962.

Camilo came back to a scene that was primed to receive him, as I wrote in an earlier article: “By the 1940s, as Panamanian society and culture began to consolidate after the waves of immigration from the construction of the Canal, the great majority of the music consumed on the radio, in cabarets, theaters and via 78 and soon 45 and 33rpm records was Cuban music. Per the writer Plinio Cogley, probably 70% of the music consumed in Panama was Cuban music.”

This man was a legend. It’s almost as if Mariano Rivera had left the Yankees at his peak to come play in Panama. But as veteran AfroCuban music journalist Lil Rodriguez has pointed out about the many brilliant Venezuelan musicians who stayed put during the Salsa boom of the ’70s and did not go seek fame in NY – if the local scene was deep and fruitful enough, why move to NYC or Mexico City?

Camilo recorded with the number one big band in Panama, Armando Boza’s Perfecta, and became the main singer with another top level Orquesta led by Marcelino Alvarez. He sang with Angelo Jaspe’s, Clarence Martin’s and Raul Ortiz’s Orquestas, and recorded with the Guardia Nacional’s Orquesta 11 de Octubre. His presence was clearly a great boon to the scene in Panama, which I have been helping to document with this blog.

I mentioned El Gran Camilón was an idol of Ismael Rivera, here they are singing together in Panama in 1970 (Maelo used to hide out in Panama all the time, and his epic hit “El Nazareno” is based on his experience visiting the Black Christ of Portobelo, patron saint of maleantes).

Camilo Rodriguez passed away in 1985 in Panama at the age of 76.

Many thanks to Harry Sepulveda, Mario Garcia Hudson, Francisco Bush Buckley QEPD, Anel Sanders and los Pelaos del Minimax.